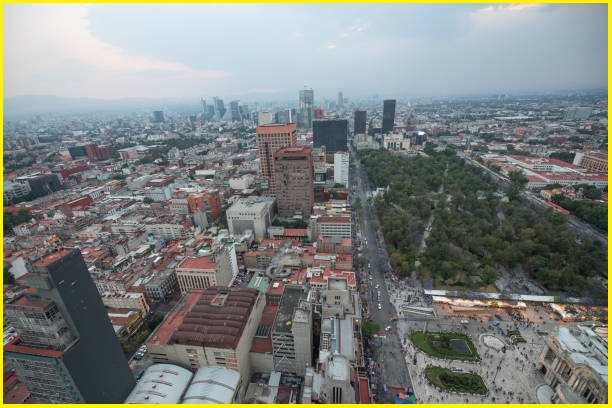

Mexico City sinking

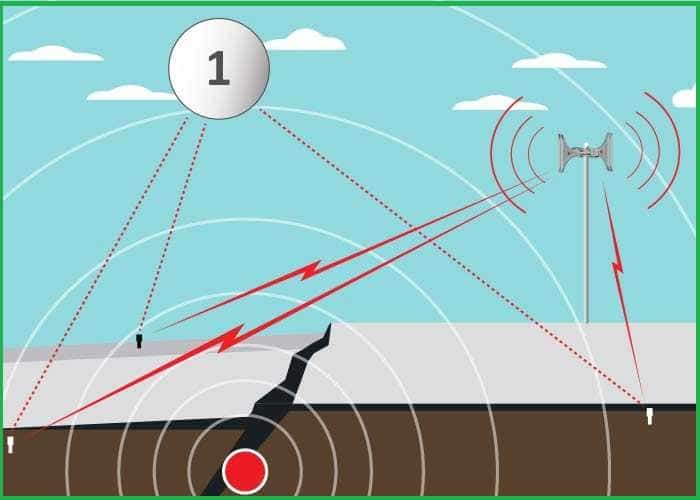

The ground in Mexico City is sinking at a rate of nearly 50 centimeters (20 inches) per year, and this subsidence is expected to continue without any recovery, according to a new study by Chaussard et al. Using 115 years of ground-based data and 24 years of satellite measurements, a team of U.S. and Mexican scientists has determined that large areas beneath Mexico City are steadily compacting after having been drained of water long ago. They predict that this compaction will continue for about 150 years, potentially adding up to 30 meters of subsidence on top of the several meters already recorded during the 20th century.

Unlike subsidence in many other cities, Mexico City’s sinking isn’t closely linked to current local groundwater pumping rates. Instead, it is due to the gradual compaction of the ancient lake bed on which the city is built. This lake bed was once Lake Texcoco, the site of the Aztec city Tenochtitlán. As water extraction pushed groundwater deeper underground, the 100-meter-thick, salty, clay-rich lake bed dried out. The fine mineral particles in the soil have been gradually compressing, leading to ongoing ground subsidence.

This type of compaction is irreversible, the researchers note, and it is causing widespread fractures that damage buildings, historical sites, sewers, and gas and water lines throughout the city. These fractures are also allowing contaminated surface water to seep into the ground, which could further complicate access to clean water in a city where it is already a challenge.

History

Densely populated Mexico City sprawls across a high-altitude lake bed, roughly 7,300 feet above sea level. Built on clay-rich soil that is now causing the city to sink, Mexico City is also highly susceptible to earthquakes and vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Today, it is likely one of the last places anyone would consider building a megacity.

The Aztecs chose this location to build their city of Tenochtitlan in 1325. when it was a collection of lakes. They established the city on an island and expanded it outward, creating a network of canals and bridges that integrated with the surrounding water.

Also read- Why The Pacific Ocean Is Shrinking and The Atlantic Ocean Is Widening

However, when the Spanish arrived in the early 16th century, they dismantled much of the Aztec city, drained the lakebed, filled in the canals, and removed the forests. They viewed water as “an enemy to overcome for the city to thrive,” explained Jose Alfredo Ramirez, an architect and co-director of Groundlab, a design and policy research organization.

Subsidence Leading to extensive damage

Many cities have experienced subsidence, but Mexico City’s situation is extreme. Venice, for example, sank about 9 inches over the 20th century due to a drop in its water table. In contrast, Mexico City has sunk 30 feet.

The subsidence has not been uniform, leading to extensive damage over the years, especially in the colonial-era city center. In response to severe cracking and the threat of further damage, scaffolding has been erected to support the walls and ceiling of the National Cathedral, the largest and oldest in Latin America, while a costly and complex effort is underway to stabilize its foundations. Across the Zocalo plaza, the National Palace has begun to tilt dangerously, with architects working to keep one wing attached to the rest of the building.

Visible evidence of this sinking can be seen along Line 2 of the city’s Metro. This subway line, which runs above ground along Tlalpan Avenue south of the city center, was perfectly level when it was built in the mid-1960s. Now, the tracks resemble a roller coaster. After subsidence damaged hundreds of irreplaceable colonial churches and mansions, the city halted water pumping in the city center and began drawing water from wells on the outskirts. This change has slowed the sinking in the city center to about an inch per year. However, some suburbs, which rely heavily on wells, continue to sink 18 to 24 inches annually.